Cleanliness, a corollary of domestic hot water usage, is estimated to account for about 6% of the

Technologists will help us address the first three of these. Just last week we had five cold calls from gentlemen with suave estuary accents offering to retrofit our domestic boiler with a certified wooden pellet burner and a Smart System to pre-warm the bath mat with waste heat from our fridge. The double-glazing salesman bounces back. But you might not like the cost of the Deluxe Bathroom Eco-Retrofit, when you compare it with a week in the

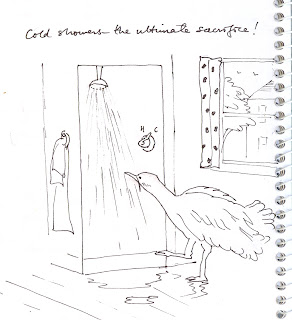

Washing at a lower temperature is really tough. We can attempt many sacrifices in order to be kinder to the planet. Surely the hardest of all is to bathe in cold water. Cold showers built the

While we are waiting for a tougher-skinned generation to emerge, our last option is to wash less. If we showered once every two or three days instead of once a day, we would make substantial inroads into emissions from domestic washing. There is no shortage of cosmetics which can offset any side-effects of infrequent washing.

At this juncture of the morning ablutions we might consider how pricing of carbon dioxide emissions fits into the bathing decision framework. The theory goes that the cost of carbon dioxide will be incorporated into the cost of fuel. At a certain price of CO2 the fuel bill will be so high that the householder should start to consider one of the five showering alternatives listed above.

I wonder what the price of CO2 would have to be for the householder to consider spending a thousand pounds or more on a renewable energy efficient shower, not to mention suffering the hassle of having workmen in. When would spending a fortune on a smart shower system be preferable to spending the same amount of money on a holiday in the sun? An astounding level of conscientiousness, wealth, farsightedness, or altruism is implied in a decision voluntarily to cut emissions from washing.

This little analytical exercise can be carried out for most aspects of our daily lives and will always lead to a similar, scary, conclusion: we can price CO2 but we have not scratched the surface in figuring out how to implement in the short-term large scale cuts in emissions across society.

Wesley, if apprised of climate change, would surely have given up some of his brevity for the sake of greater moral precision and adopted a practical policy stance: “Moderate grubbiness is next to Godliness, unless you can handle a cold shower.”